Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré

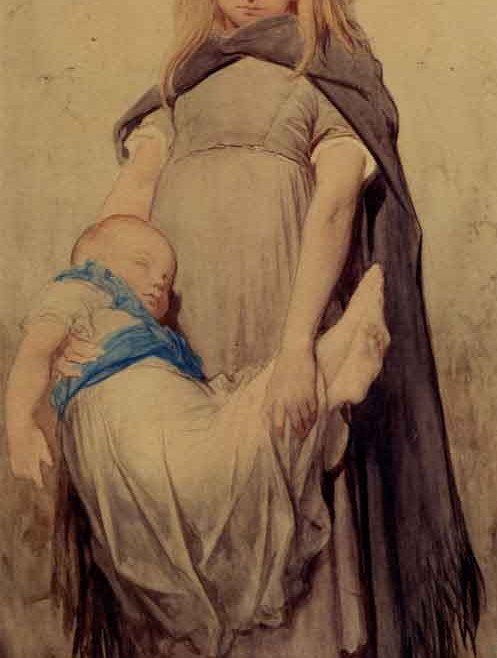

https://linesandmarks.com/wp-content/uploads/guistav-dore-young-beggar.jpg 497 1000 Lines & Marks Lines & Marks https://linesandmarks.com/wp-content/uploads/guistav-dore-young-beggar.jpg``I have been told for a long time that painting would make me despair of life.``

Gustave Dore,”The Hare and the Frogs.” Engraving, 1868.

Left side: “Paolo and Francesca da Rimini.” Oil on canvas. | Right side: “The Inferno, Canto 5.” Etching.

Doré was born in Strasbourg on 6 January 1832. By age five, he was a prodigy troublemaker, playing pranks that were mature beyond his years. Seven years later, he began carving in cement. At the age of fifteen Doré began his career working as a caricaturist for the French paper Le Journal pour rire, and subsequently went on to win commissions to depict scenes from books by Rabelais, Balzac, Milton and Dante.

In 1853, Doré was asked to illustrate the works of Lord Byron. This commission was followed by additional work for British publishers, including a new illustrated English Bible. In 1856 he produced twelve folio-size illustrations of The Legend of The Wandering Jew for a short poem which Pierre-Jean de Ranger had derived from a novel of Eugène Sue of 1845.

In the 1860s he illustrated a French edition of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and his depictions of the knight and his squire, Sancho Panza, have become so famous that they have influenced subsequent readers, artists, and stage and film directors’ ideas of the physical “look” of the two characters. Doré also illustrated an oversized edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”, an endeavor that earned him 30,000 francs from publisher Harper & Brothers in 1883. (wiki)

[foogallery id=”7312″]

Gustave Doré, “The Martyrdom of the Holy Innocents,” 1868.

[foogallery id=”7387″]

Doré’s illustrations for the English Bible (1866) were a great success, and in 1867 Doré had a major exhibition of his work in London. This exhibition led to the foundation of the Doré Gallery in Bond Street, London. In 1869, Blanchard Jerrold, the son of Douglas William Jerrold, suggested that they work together to produce a comprehensive portrait of London. Jerrold had obtained the idea from The Microcosm of London produced by Rudolph Ackermann, William Pyne, and Thomas Rowlandson in 1808. Doré signed a five-year contract with the publishers Grant & Co that involved his staying in London for three months a year, and he received the vast sum of £10,000 a year for the project. Doré was mainly celebrated for his paintings in his day. His paintings remain world-renowned, but his woodcuts and engravings, like those he did for Jerrold, are where he really excelled as an artist with an individual vision.

The completed book, London: A Pilgrimage, with 180 engravings, was published in 1872. It enjoyed commercial and popular success, but the work was disliked by many contemporary critics. Some of these critics were concerned with the fact that Doré appeared to focus on the poverty that existed in parts of London. Doré was accused by The Art Journal of “inventing rather than copying.” The Westminster Review claimed that “Doré gives us sketches in which the commonest, the vulgarest external features are set down.” The book was a financial success, however, and Doré received commissions from other British publishers.

Doré’s later work included illustrations for new editions of Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Tennyson’s The Idylls of the King, The Works of Thomas Hood, and The Divine Comedy. Doré’s work also appeared in the weekly newspaper The Illustrated London News.

Doré never married and, following the death of his father in 1849, he continued to live with his mother, illustrating books until his death in Paris following a short illness. The city’s Père Lachaise Cemetery contains his grave. The government of France made him a Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur in 1861. (wiki)

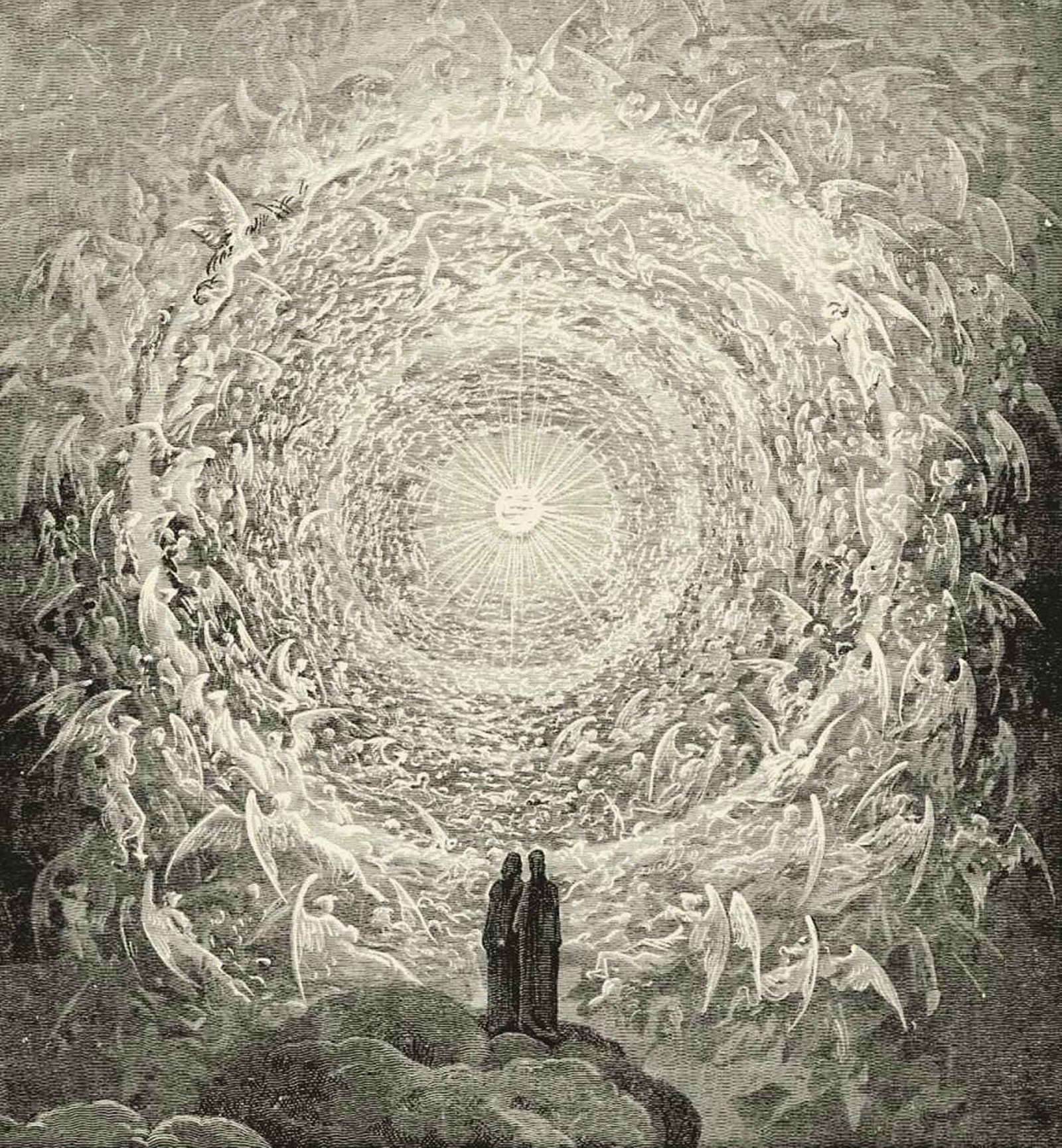

Gustave Dore, “The Descent Of The Spirit.”

Top: “The Neophyte.” Oil on canvas. | Bottom: “The Neophyte.” Pencil.

post-ussr kid

no-roots tree.