Soviet Propaganda and Anti-Religious Campaigns

https://linesandmarks.com/wp-content/uploads/viktor-deni-1st-mai-poster-1929.jpg 700 940 Lines & Marks Lines & Marks https://linesandmarks.com/wp-content/uploads/viktor-deni-1st-mai-poster-1929.jpgTo win in the civil war, the sprouting Soviet power had to ensure it was supported by the workers and the peasants. How could they show the illiterate population that the Bolsheviks were on their side? With a bright poster and a catchy slogan…Soviet propaganda found the soft spots of the powerless poor people, and the outstanding artists of the Russian avant garde helped attack them.” – From Bird in Flight, “The Early Days of Soviet Propaganda.”

[foogallery id=”8613″]

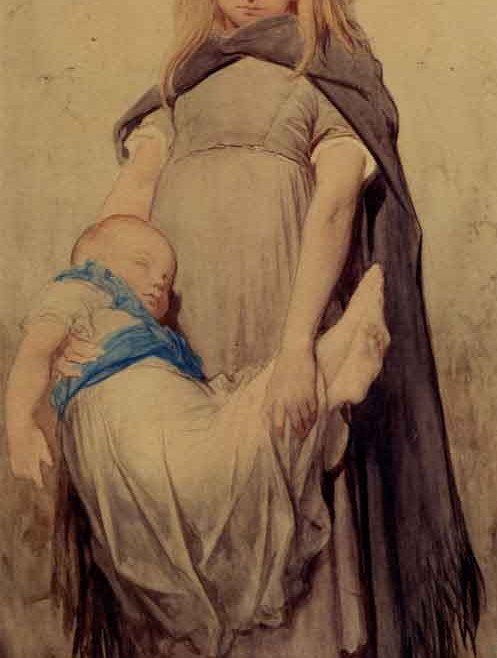

The Soviet Union was the first state to have as an ideological objective the elimination of religion. Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in the schools. Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed.

The main target of the anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and 1930s was the Russian Orthodox Church, which had the largest number of faithful. Nearly all of its clergy, and many of its believers, were shot or sent to labor camps. Theological schools were closed, and church publications were prohibited. By 1939 only about 500 of over 50,000 churches remained open.” – From the Library of Congress, Revelations from the Russian Archives, Anti-religious Campaigns.

[foogallery id=”8615″]

[foogallery id=”8621″]

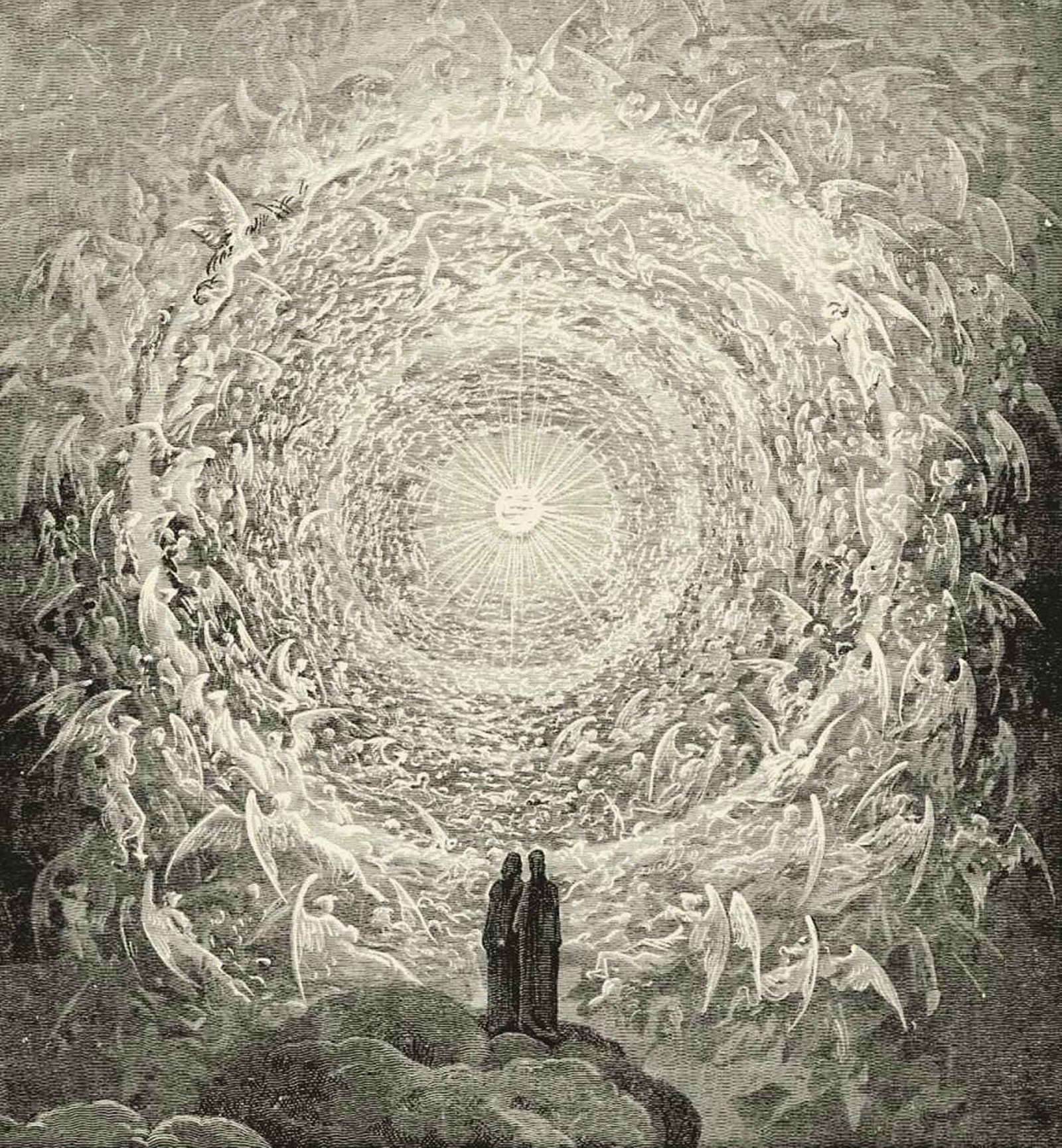

post-ussr kid

no-roots tree.