Marcel Dzama

Interview

Once it comes to life, it’s like wow, that really happened from just a doodle on a page.

N.A.S.A. “The People Tree,” featuring David Byrne, Chali 2na, Gift Of Gab & Z-Trip. Directed and Animated by Syd Garon and Johannes Gamble. (2009)

L&M: Your work depicts bats, bears, ghosts, polka-dotted dancers, military personnel, terrorists, trees, fetuses, cowboys, hung-men, decapitated heads, gangsters, and all sorts of creatures – all set against the backdrop of a bustling, erotically charged, violent world. Where did the early characters come from? How do new characters appear on the scene and who decides if they get to stay, you or them?

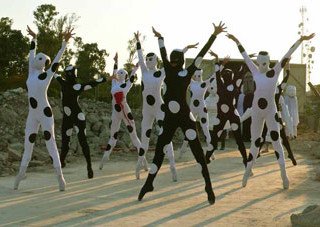

MD: (laughs) I guess when a character is repeated a lot, it’s kind of like my go to character at the time, so it comes out in a series at least for a few years, and then some other character will be the next one. A lot of them came from, like especially the early ones like the bat character, I was using it as a symbol for a fascist army at the time, and then later it I think I changed it to a rebel army, maybe even before that the bat was in the drawing just ‘cause I was fascinated by bats, seeing them in Winnipeg, and then probably being into Batman as a little kid too. The polka-dotted character was a straight reference from PicabiaFrancis Picabia Francis Picabia, "Projet de costume pour relache borlin." (1924) Ballet conceived in French in 1924 in Paris written by Francis Picabia , also decorator, choreographed by Jean Börlin , all to the music of Erik Satie. (wiki). In the first drawing I was actually referencing that piece he had done and then after that I kind of just took it over. I thought it was kind of a nice way of changing the hooded terrorist outfit, making it more like a clown’s outfit.

Francis Picabia, "Projet de costume pour relache borlin." (1924) Ballet conceived in French in 1924 in Paris written by Francis Picabia , also decorator, choreographed by Jean Börlin , all to the music of Erik Satie. (wiki). In the first drawing I was actually referencing that piece he had done and then after that I kind of just took it over. I thought it was kind of a nice way of changing the hooded terrorist outfit, making it more like a clown’s outfit.

L&M: You also reference Picabia’s “Adoration of the CalfFrancis Picabia Francis Picabia, "Adoration of the Calf." (1941-1942)” a lot.

Francis Picabia, "Adoration of the Calf." (1941-1942)” a lot.

MD: Yeah, quite a bit. In the film there’s the whole birthing scene. I was thinking of Picabia giving birth to Marcel Duchamp, ‘cause I kind of felt like once Duchamp met Picabia, that’s when Duchamp actually got interesting as an artist, for me anyway. So I kind of felt like he gave birth to the Duchamp I like. (laughs) I forget what other characters you said, but the tree was from seeing old trees in Winnipeg, also the Wizard of Oz treeThe Wizard of Oz The Forest of Fighting Trees in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz reside in Quadling Country. Dorothy Gale, Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion had to go through the Forest of Fighting Trees in order to get to Glinda the Good Witch. Tin Man used his axe on the Fighting Trees. In the 1939 film version, apple trees become annoyed with Dorothy when she picks an apple from one of them. The Scarecrow helps by provoking the apple trees into throwing their apples at him, which Dorothy can then collect. (wiki) and Dantes InfernoDante"s Inferno, 7th Circle of Hell

The Forest of Fighting Trees in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz reside in Quadling Country. Dorothy Gale, Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion had to go through the Forest of Fighting Trees in order to get to Glinda the Good Witch. Tin Man used his axe on the Fighting Trees. In the 1939 film version, apple trees become annoyed with Dorothy when she picks an apple from one of them. The Scarecrow helps by provoking the apple trees into throwing their apples at him, which Dorothy can then collect. (wiki) and Dantes InfernoDante"s Inferno, 7th Circle of Hell The suicides – the violent against self – are transformed into gnarled thorny bushes and trees and then fed upon by Harpies. The trees are a metaphor for the state of mind in which suicide is committed. Dante learns that these suicides, unique among the dead, will not be corporally resurrected after the final judgement since they gave away their bodies through suicide., the 7th circle of hell – the people that commit suicide became these immovable suffering trees.

The suicides – the violent against self – are transformed into gnarled thorny bushes and trees and then fed upon by Harpies. The trees are a metaphor for the state of mind in which suicide is committed. Dante learns that these suicides, unique among the dead, will not be corporally resurrected after the final judgement since they gave away their bodies through suicide., the 7th circle of hell – the people that commit suicide became these immovable suffering trees.

L&M: Do characters always have a specific meaning? Like you said earlier that bats represented a fascist or rebel army.

MD: No, it’s just like that for that drawing and then after that it could be anything in the next one.

L&M: The symbolism of the character changes.

MD: Yeah, otherwise it would just be really messed up hieroglyphics. (laughs)

L&M: You’re influenced by a lot of people such as Picabia and Duchamp, but what is it about Goya specifically that affected you? He seems to come into play a lot in your artwork, titles, and in tone a bit.

MD: With his prints for sure, I almost feel like they could be a part of this whole world. They’re so surreal to begin with, and they have that mix of reality with the supernatural, and they’re dealing with large subject matters. Once I saw his work I could relate to it instantly, especially the prints, and also his dark period paintings too. Also the witchcraft kind of things, they could be part of it as well. With Duchamp I guess that was just from an early age, having the same name and being really confused by his work and then later seeing it in person when I moved to New York. And going to Philadelphia and seeing it and being fascinated by it.

L&M: And you’ve said your first childhood experience seeing Duchamp’s “Étant donnés” disturbed you.

MD: Yeah, and then kind of having it as a memory. But then once seeing it in person it really was like, oh yes I want to know everything about him. Probably I was too in to it, (laughs) but I think it’s ok. Seems like a lot of artists are anyway. (laughs)

Marcel Dzama, Diorama, “On the banks of the Red River.” (2008) Wood, glazed ceramic sculptures, metal, and fabric. 86 x 253 x 97 inches (218.4 x 642.6 x 246.4 cm). Edition of 3 + 2 APs.

…the work was much more violent, definitely during the Iraq war.

L&M: Your drawings have an old-timey feel, like drawings from the first half of the 20th century. You also seem to resist new technologies, favoring the “intimacy” of paper and pencil, and objects – tangible, physical things. Even in your more technologically dependent productions with film and music, they still heavily reference old films from the 20’s, and in that spirit, you even performed the music score liveKunstwerk, Berlin Marcel Dzama performing the music score for “Une Danse Des Bouffons (A Jester"s Dance),” at Kunstwerk, Berlin. (2015) for your film, “Une Danse Des Bouffons,” at Kunstwerk in Berlin. What is this fascination with the look and feel and events of the past, or at least a pre-digital age?

Marcel Dzama performing the music score for “Une Danse Des Bouffons (A Jester"s Dance),” at Kunstwerk, Berlin. (2015) for your film, “Une Danse Des Bouffons,” at Kunstwerk in Berlin. What is this fascination with the look and feel and events of the past, or at least a pre-digital age?

MD: I watched a lot of early WWI and WWII films as a kid. My dad was kind of fascinated by them. And then a lot of, not only documentaries, films dealing with that time period, and they were much more sophisticated than what I was watching on my own, so those for sure would get into my consciousness. And I think the whole Dada art movement, I felt that was the closest thing to what I was trying to do as an artist. I guess probably just being influenced by that artwork as well, and probably the few books I had at the beginning – my grandparents had this set of Time Magazine books that were about each decade, like the aughts, then teens, then 20’s, 30’s and 40’s. I’d always look at those and they would always spark ideas for drawings.

L&M: Do you carry a nostalgia for an older time, a time when things were more simple, or at least more analog?

MD: Yeah I think for some of it, but it was a terrible time period as well. I think right now in some ways I do like our time period as well. (laughs) I go back and forth all the time. But for sure the clothes people wore were much more, as a fashion point, I just find it much more interesting to see these kinds of, especially the 1920’s clothing. And the whole Suffragette movement was really inspiring so I think that influenced the early work for sure.

I’m trying to think of what else I was drawing in the early days. I guess even now a lot of those uniforms come up. Now they’re more costumey though. They kind of look more like a weird mix of a Shakespearian play and WWII uniforms, and I don’t know, clown outfits, (laughs) and a Bauhaus mask.

L&M: Speaking of this change from uniform to costume, you’ve also mentioned how your characters used to be more human-animal hybrids, but now they’re more wearing costumes. Also, you’ve said since the birth of your child your work is less violent. What else has changed in the work from the very early days to now?

MD: Yeah, like what you were saying, the work was much more violent, definitely during the Iraq war. I mean it was violent before that but then it got a little more political as well. I’m sure [violence] will still come into play. (laughs) It was definitely more minimal at the beginning, it was just like usually one character or so, maybe interacting with two. And then moving to New York also, claustrophobia came into it in some ways, usually at least 6 characters on a page and the subject matter. Yeah, I feel, whatever interests I have come out during those times.

I don’t mind how people see the drawings. I’d prefer if it was in a deeper way, but it’s nice just seeing them existing.

L&M: You collaborate often with others in film and music, but you also like to work alone. Do you prefer the solitude more or the shared experience?

MD: I find it much more fun collaborating. Even if you’re drawing next to someone who’s also drawing, even if you’re not working on each others art, it’s just nice to have company, and you can work out ideas with each other. I guess the advantage of being solitary is you can work at weird hours. (laughs) You don’t have to rely on the other person being able come. Being in an art group was great for finding new ways of working. You can experiment in styles that, at least I did when I was in the Art Lodge, I wouldn’t really associate with my own work, and then kind of honing in what I liked about it and what I didn’t. It’s a good place to discover new ways of working. Sometimes when I’m just working on my own, you get less experimental maybe. At least when I was working in the Art Lodge as an art group, you kind of lose your own ego, and it’s just more of the group, so you could really work in any style. It was author-less.

L&M: You’ve talked about when you were making drawings with Maurice Sendak and Spike Jones, you were trying to shock each other and that made the work more perverse. In this sense was the collaboration pushing your boundaries more than when you work alone?

MD: Yeah that’s true. I guess it’s different with every collaboration. With that I was laughing so much my face hurt by the end of the day trying to out do each other. And then with others it’s just been fun to have company and bounce off ideas. And with film it’s really amazing to collaborate with other people ’cause there’s just so much I wouldn’t have understood or been able to do, especially with a choreographer or say a costume designer, making things that I could draw but I couldn’t fabricate. ‘Cause at the beginning when I made short films I would be making all these costumes and they were pretty limited and also the amount of time they took – I didn’t want to spend it all making costumes. It’s nice to have a group of people to work with as well.

L&M: And what about in the case of let’s say “Une Danse des Bouffons” where you performed live with Jeremy Gara of Arcade Fire? Or the music video for Will Butler’s “Something’s Coming”? How does that kind of collaboration work?

MD: Oh yeah, that’s amazing working with the Arcade Fire musicians. They’re just so talented and any slight idea I had, like I could just say I want a drum beat like this, and they’d come up with something much better. That was really exciting, but I’m sure I learned a lot more than they got out of the experience. (laughs)

L&M: With some of these collaborations, your characters are now entering other worlds, like you showed up in one of your costumes in Jay Z’s music video, “Picasso Baby,” and I see your characters showing up more in music videos and film.

MD: Yeah, the whole fun thing about doing film is usually a lot of the scenes are based on drawings that I’ve done, or even other artworks. With the last film a lot of that was artwork I really wanted to see come to life. A lot of it was my own [work] and another percentage was from artists that I admire. It was really exciting to see the “Adoration of the Calf” Picabia piece come to life, or even more than that, like almost meeting Picabia or something. It was an exciting way of making art. (laughs)

L&M: As you do these collaborations, your audience is changing. Whereas before your audience was someone who would pick up an art book or go into a gallery, now it’s also Jay Z fans or the ballet. How do you hope people will respond when they see these characters for the first time out of the context of your early work? Do you want people to be amused, entertained, curious?

MD: Yeah, all of that. That would be great.(laughs) Any emotion would be nice.

L&M: Do you feel the same about the drawings as well, or do you want people to have a deeper interaction with the drawings?

MD: I don’t mind how people see the drawings. I’d prefer if it was in a deeper way, but it’s nice to just see them existing. Anytime a book is made of the artwork it’s exiting to see. It feels like they exist now or something. (laughs)

L&M: Where is your work going now? Have you exhausted this world or it just starting to mature?

MD: I don’t know. I think it’s still there right now. Especially in the last while it’s much more dance oriented and operatic so I think it’s still on that page. I haven’t ended that chapter yet I guess.

L&M: Do you see your work moving in a direction? Do you feel another change coming on, another shift?

MD: Well right now I’m working with the New York City Ballet, I’ve been doing stage design and costumes and making up characters for it as well. It’s loosely based on this Hans Christian Anderson story called “The Most Incredible Thing.” So I’ve been making costumes for that in the last little while, just drawing sketches and things. That’s what I’ve been focusing on mostly in the last bit so it’s definitely gone very heavy dance oriented. (laughs)

L&M: Maybe you’ll start a dance troupe soon.

MD: (laughs) Yeah, I’ll have to start learning choreography.

L&M: It seems like you’re having fun with all of it.

MD: Yeah, just starting from a drawing and making it come to life, that whole process. Once it comes to life, it’s like wow, that really happened from just a doodle on a page.

[foogallery id=”5593″]

[foogallery id=”5759″]

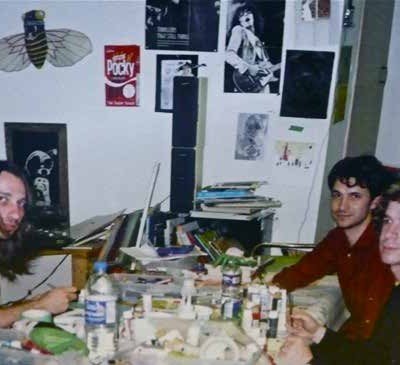

Maurice Sendak, Spike Jonze, and Marcel Dzama. (2011)

The Royal Art Lodge. Neil Farber, Marcel Dzama, and Michael Dumontier. (2002)

[foogallery id=”5665″]