Marcel Dzama

Interview

I think of it almost as Dante’s Inferno … making up my own mythology around trying to explain humanity.

Lines & Marks: You say you were drawing as far back as you can remember, but when did you start to realize that your drawings were more than just a childhood preoccupation, that they might have significance to others?

Marcel Dzama: Probably the end of grad school where I kind of figured out what I wanted to occupy my time doing. But I guess I was always doing that with small little books as a kid. I started making small little comic books, almost more like children’s books – one page and a story – and I had friends who were really excited every time I made one. I guess that kind of started it. So that would probably be the 6th grade or something.

L&M: Around 6th grade you started to have your first audience.

MD: That was the first time when my friends were excited if I brought [a book] to school and they would want to know when I was going to finish the next one. That even started other kids in the class making books and things. So we all got together in the library and started drawing. It didn’t last very long though. The next year kids were into hockey. (laughs) It was a small little moment, but an important one for me.

L&M: Did the act of drawing change knowing that you had a receptive audience? Is it different to draw when you know it will be in dialogue with the public?

MD: I try not to repeat myself knowing that there is an audience. Probably makes me slightly more ambitious too. But I think even if it was just for myself, I’d still be doing it, ’cause that part is therapy, just getting it of my system and putting it onto a page. I think originally that’s how it all kind of started anyway. (laughs) Maybe not at the very beginning but later on that’s what I found most exciting, getting the things that either disturbed or I was excited about out of my head.

L&M: If you didn’t have drawing as an outlet, where would you be today?

MD: (laughs) Without that outlet? I don’t know. probably a small-time hoodlum. (laughs) Maybe a soldier. (laughs) No, I don’t think I’d join the army. Maybe a comedian soldier. (laughs)

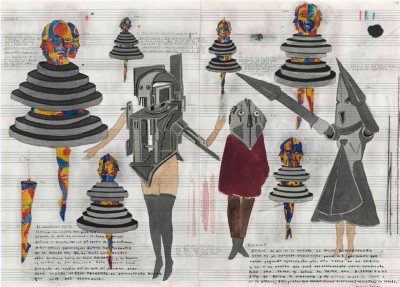

Marcel Dzama, “World Gone Wrong.” (2005) Ink and watercolor on paper. 6-part work: Overall: 28 x 33 inches. (71.1 x 83.8 cm).

Usually when there’s something I see that shocks me, I’ll end up basing drawings on it.

L&M: There seems to have been a few events in your life that have both disturbed and compelled you at the same time. In your book, “Sower of Discord,” it mentions that you were scared and fascinated by a “snarling, bestial devil” that you saw in a Christian reference book. You also had a similar reaction to first seeing as a young person, Duchamp’s “Étant donnés,” and you had a strong response to movies and documentaries about WWI and WWII, as well as concentrations camps on TV. Was this feeling of simultaneous repulsion and fascination an instigating force in your work?

MD: Definitely. Usually when there’s something I see that shocks me, I’ll end up basing drawings on it. It’s a motivator, you could say that. I think of it almost as Dante’s Inferno, or the drawingsDante"s Inferno William Blake"s image of the Minotaur to illustrate Inferno, Canto XII,12–28, The Minotaur XII for it, making up my own mythology around trying to explain humanity. [But] I find when I do try to organize the whole thing into some sort of mythology, it’s so all over the place, but I think it comes to that’s how society is. It’s not just one story, it’s so many stories happening. Things change constantly so it’s not like a tidy book or something.

William Blake"s image of the Minotaur to illustrate Inferno, Canto XII,12–28, The Minotaur XII for it, making up my own mythology around trying to explain humanity. [But] I find when I do try to organize the whole thing into some sort of mythology, it’s so all over the place, but I think it comes to that’s how society is. It’s not just one story, it’s so many stories happening. Things change constantly so it’s not like a tidy book or something.

L&M: What is your overall view on the world? Is it optimistic, or do you see the world going to hell in a hand-basket?

MD: (laughs) Yeah. Well my son is turning three tomorrow. I’ve been trying to look at the bright side of things more. He changed me. Before I was much more negative. I just felt like my friends were passing away and time was just disappearing and the world leading us to our graves. But having a child you realize, the obvious thing, the whole cycle of life. But before I saw the negative end part and not the beginning so much.

L&M: How has this found it’s way into your drawings, this change in perspective?

MD: I find that dance has come in to play a lot in the last maybe five years and I think it’s gotten to be more of some sort of weird celebration, in some of them anyway, some sort of weird old 1920’s musical with tons of dancing characters. I mean they’re doing strange things usually, but there’s more of some kind of celebration going on there.

To put order to all that chaos I put all the characters into some pattern, and I felt like dance was the best way to do it…

L&M: There’s a lot of dancing in almost all of your work in every medium. What is the significance of dancing?

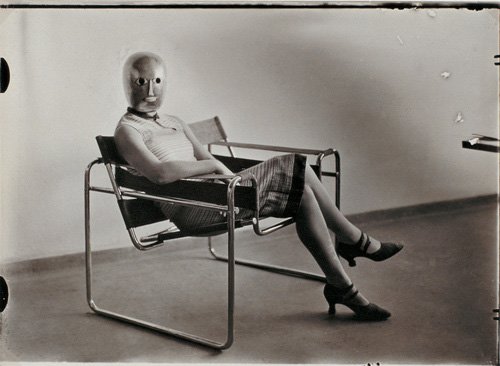

MD: I like the idea of movement more. Before the figures were just sitting there, I don’t know, shooting probably. (laughs) Coming to New York [the drawings] became claustrophobic ’cause I was living in Manhattan, just off of Union Square, and every day as soon as I walked out the door there were tons of people, so it kind of changed the look of the drawings. To put order to all that chaos I put all the characters into some pattern, and I felt like dance was the best way to do it, kind of like some organizational tool. But also I had a few old dance magazines and got into Oskar Schlemmer and he had these crazy costumes that he made for a few ballets. And I saw a short film, a remake in the 70’s of Triadic Ballet. It had these modernist costumes and at the time I was kind of drawing that style anyway so it kind of really went together well and influenced my work.

L&M: Having dyslexia you gravitated more to pictures, but generally speaking, what did depicting the world via drawing allow for that other mediums did not? Do you find you can express yourself best via drawing, or do the other mediums you work with allow for things that drawing doesn’t?

MD: I find that drawing is the tool I go to first for everything. I was never good at the written word for expressing myself at all. I did bad poetry and stuff like that, (laughs) just for maybe songs or something or trying to be poetic I guess. (laughs) And then later on actually some of the bad poetry turned into titles for drawings so that was kind of funny. Yeah, I find that drawing is the medium I’m definitely the most comfortable in so it’s the one I feel expresses my ideas the best. It’s true that with film I find that, it just reads in such a different way. After I’m finished with a film I’m kind of fascinated that I actually did it, (laughs) more than drawing ’cause it’s such a collaborative effort.

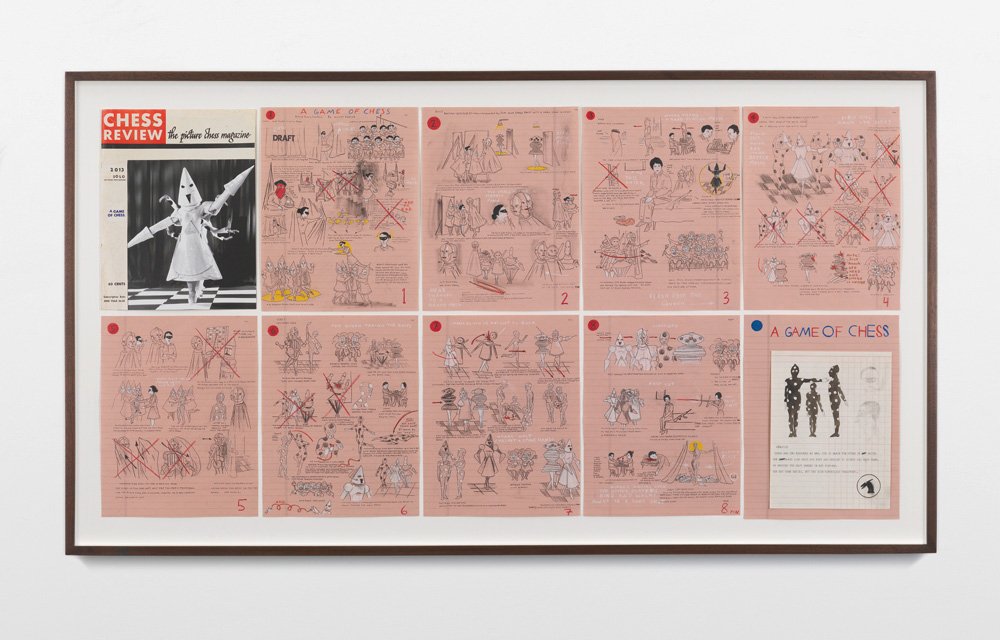

L&M: What is the relationship between drawing and the other mediums you work with. For example, some drawings make their way into dioramas, and in the film, “A Game of Chess,” the costumes you made worked their way back into the drawings.

MD: Most of the time everything is drawn out. I even do storyboards sometimes before I do the script. It’s easier for me to tell the story in visuals than writing it down. Sometimes when I’m finished with a film I like to use some of the characters. Some characters will be organically made for the film, like I’ll have some beaten up mask and I’ll change it up quickly. I’ll put some horns on it or something, put some fur and crazy looking eyes, and later on I’ll draw it after the fact.

L&M: Why is the act of physically drawing, which you often describe as an intimate process, so important to you in an ever increasing digital age?

MD: Like what you’re saying, the intimacy of it. Any other medium I was into I lost that a little bit. I think it’s, for me for sure, I mean maybe besides performance art, it’s the most personal thing.

L&M: Do you find that drawing, along with other analog activities, is diminishing as we progress with digital technology?

MD: Yeah I think it can, for a time. I think people are starting now to reject a lot of the digital. There’s an embrace of analog. People are moving back, realizing that the intimacy is lost. Seems like there are a few books out there about turning off your cellphone (laughs) and there are a lot of self-help books about turning off technology.

I find whenever I do have to use the computer a lot or write a lot of emails, I’m not living in the moment at all. Like when I’m hanging out with my son, I’m thinking I’ve got to get these emails done, and not enjoying playing in the park with him or something. I find that I am living in the moment when I’m doing a drawing. Maybe I’m thinking of the end-piece, but time kind of disappears for me.

L&M: What is your daily practice? Do you draw every day? Do you have certain hours? Now that you have a family and a demanding professional life, do you have a routine, or do you just try to get to drawing whenever you can?

MD: Yeah I have kind of a routine. I spend most of the day with my family, not working so much, maybe doing a few random emails or phone calls and things like that. But once my son goes to bed I start working at night. But I’ve always worked at night even before he was born. I always felt the most creative in the late hours.

L&M: But having a son now, that means you can’t really sleep in.

MD: (laughs) Yeah, I’m much more tired. It takes me a lot longer to finish something now. (laughs) Somewhere in there I try to take a nap to make up for the few lost hours, but I don’t need too much time to sleep. I usually sleep only 5 hours or something. There are times I allow myself to sleep but I’m thinking of projects and ideas. I feel like I gotta use this time.

L&M: Do you think there could be a period of time where didn’t draw? If you couldn’t draw for a length of time do you think you would go mad?

MD: Now that I have my son I don’t think so. I would just focus on that. ‘Cause playing with him feels very creative. Usually I have to think of some weird scenario for whatever toy he’s into at the time, or a game playing different characters, dressing up weird. (laughs) He’s very creative on his own too. My favorite time is listening to him play by himself, hearing his scenarios of stories as talks them out.

[foogallery id=”5413″]

“Das Triadische Ballett,” by Bavaria Atelier GmbH, with live-action dancers and new music by Erich Ferstl. (1970)

Marcel Dzama, “A Game of Chess.” (2011) Full Film from Sies + Höke.

Marcel Dzama with son setting up for “Une Danse des Bouffons (A Jester’s Dance)” at David Zwirner Gallery, New York. (2014)

Oskar Schlemmer Mask, c.1926