Marcel Dzama

Interview

I like the whole idea of destroying whatever I was working on last and then making something new from it.

L&M: “Une Danse Des Bouffons” is literally about rebirth – it was gross, yet strangely compelling to watch a full-grown man being reborn born out of a giant cow’s “chest vagina” – twice.

MD: (laughs)

L&M: Also your work “Grand Presentiments of What Must Come” is drawn on music from “Auld Lang Syne” – the song itself, as quoted in “Sower of Discord,” is “generally associated with endings and beginnings” and you mentioned that the coming birth of your new child represented “beginning a new chapter in life.” The 1996 fire that burned most of your life’s work till then, you also saw as a “a Phoenix story.” How does rebirth figure into your personal life, and of course, in your work?

MD: Yeah, it feels like it’s definitely something that’s a theme in almost all the work. Anything on a larger scale for sure, like a film or a larger drawing. It feels like the classic story in most mythologies. I’ve always been attracted to that.

L&M: What about in life?

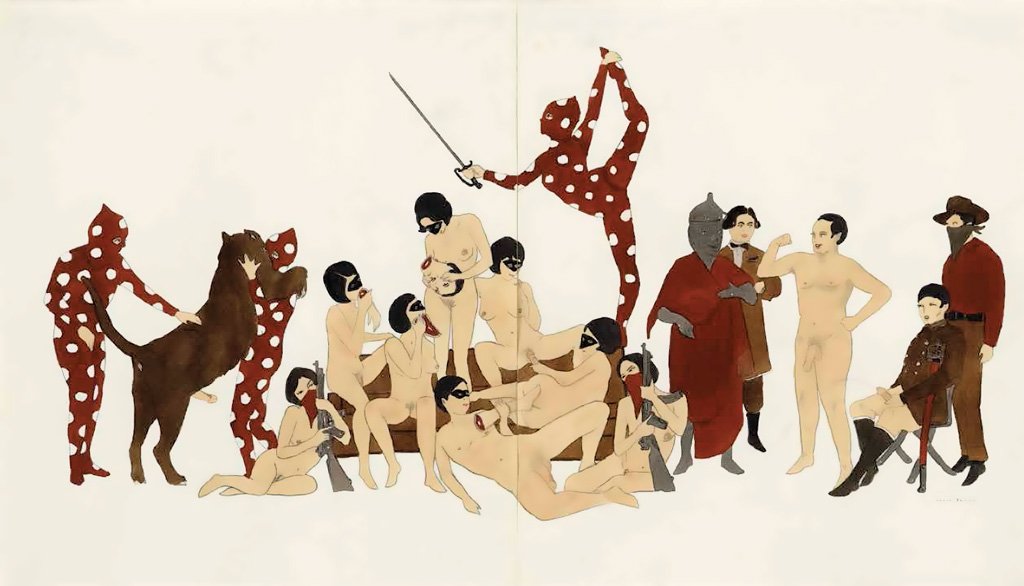

MD: Yeah, moving for sure. Moving from Winnipeg to New York really felt like that’s when I decided to change. I made this drawingMarcel Dzama, "You gotta make room for the new ones." (2005) Ink and watercolor on paper. 2-part work. Overall: 14 x 22 inches (35.6 x 55.9 cm). Each: 14 x 11 inches (35.6 x 27.9 cm)., it has all these hunters killing off all these animals, and it kind of felt like it was a big change in my work. That’s when the work kind of went a little bit political at the time, just being more aware of the propaganda machine around me. (laughs) And then spending half a year in Mexico. That changed my work quite a bit.

Ink and watercolor on paper. 2-part work. Overall: 14 x 22 inches (35.6 x 55.9 cm). Each: 14 x 11 inches (35.6 x 27.9 cm)., it has all these hunters killing off all these animals, and it kind of felt like it was a big change in my work. That’s when the work kind of went a little bit political at the time, just being more aware of the propaganda machine around me. (laughs) And then spending half a year in Mexico. That changed my work quite a bit.

L&M: They practice death celebrations there as well.

MD: Yeah, exactly, they have the Day of the DeadDay of the Dead Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos) is a Mexican holiday celebrated throughout Mexico, in particular the Central and South regions, and acknowledged around the world in other cultures. The holiday focuses on gatherings of family and friends to pray for and remember friends and family members who have died, and help support their spiritual journey. (wiki) and they have this other celebration where they blow up these piñata sculptures of Judas"Hanging of Judas"

Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos) is a Mexican holiday celebrated throughout Mexico, in particular the Central and South regions, and acknowledged around the world in other cultures. The holiday focuses on gatherings of family and friends to pray for and remember friends and family members who have died, and help support their spiritual journey. (wiki) and they have this other celebration where they blow up these piñata sculptures of Judas"Hanging of Judas" "Hanging of judas" by Bain News Service. (early 20th century) The burning of Judas is an Easter-time ritual in many Orthodox and Catholic Christian communities, where an effigy of Judas Iscariot is burned. Other related mistreatment of Judas effigies include hanging, flogging, and exploding with fireworks. (wiki) which is really fascinating. I like the whole idea of destroying whatever I was working on last and then making something new from it.

"Hanging of judas" by Bain News Service. (early 20th century) The burning of Judas is an Easter-time ritual in many Orthodox and Catholic Christian communities, where an effigy of Judas Iscariot is burned. Other related mistreatment of Judas effigies include hanging, flogging, and exploding with fireworks. (wiki) which is really fascinating. I like the whole idea of destroying whatever I was working on last and then making something new from it.

L&M: Do you remember a certain point in your life where you became aware of the idea of rebirth? When did you start to think about all this?

MD: Well the main moment in my life I really felt the rebirth scenario and which made me think a lot about it, I had a house fire in ’96 and pretty much all of my artwork was destroyed. My main possessions were destroyed too. I kind of felt relieved from it. I thought I’d be depressed that I lost everything. I mean there was that depression too but there was also this weight off my shoulders as well. And I kind of also found my voice art-wise. That’s when I started making small drawings on hotel stationery. Before I was doing these messy large paintings on board. And this is all in art school. And I would just bring to my crits these drawings I had done on stationary and on whatever paper I had around. I was staying at this hotel called the Airliner Inn and it had the little Airliner Inn symbol at the top of it. That was probably the real first moment where I thought of the whole rebirth scenario, after it all ended, when it was over. It really was the first time I realized nothing is permanent. Things can change on a dime. Your whole reality can change.

L&M: You’ve experienced a lot of death in your life, and lot of suicides. You witnessed a hanging as well, after the fact. Did those events make you think about rebirth?

MD: I was a teenager mainly. But I didn’t think of the rebirth idea of it with that. That was more just depressing. I think until my son was born that’s when I would be at my darkest, when I found out someone had passed away. I mean it still is terrible, but I guess now I see the bigger picture. (laughs)

Marcel Dzama, Behind the Scenes of “Une Danse des Bouffons.” Powdering the “chest vagina.” (2015)

Marcel Dzama, Trailer, “Une Danse des Bouffons (A Jester’s Dance).” (2013) (Starring Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, Hannelore Knuts & Jason Grisell. Songs by Will Butler, Jeremy Gara, Tim Kingsbury, and Marcel Dzama)

Public execution by the Nazis near Płaszów-Prokocim train station in Krakow, 26 June 1942

I think that probably everyone has these thoughts at some point, they just don’t draw them.

L&M: You work is often described as “morbid” or “macabre.” Do people try to psychoanalyze you, or do you fear they will? Do you ever wonder yourself from where some of the more disturbing images come from?

MD: (laughs) Yeah there’ve been a few moments where I’m like, What am I doing? There’ve been a few drawings where I’m like, should I show this to anyone? (laughs) Or do they go into the to-be-destroyed pile? (laughs)

L&M: Do you ever get feedback which you feel is too direct?

MD: Sometimes I feel sorry for my wife, for the highly sexual ones. (laughs) She gets asked about that sometimes. (laughs) Um, sure, there are people analyzing it, but I feel that it comes more out of the surrealist movement, using your subconscious more. I don’t how much of that is the person you are, but maybe it is, I don’t know. (laughs) I think that probably everyone has these thoughts at some point, they just don’t draw them. (laughs)

L&M: The work obviously comes from a personal place, but are you also trying to touch on universal themes?

MD: I find when I do try to organize the whole thing into some sort of mythology, it’s so all over the place, but I think it comes to that’s how society is. It’s not just one story, it’s so many stories happening. Things change constantly so it’s not like a tidy book or something. It’s like a feeling you can’t describe. Like when you read a good poem. In some ways you kind of feel what they’re saying more than what they say.

L&M: I suppose if you could say it then there’d be no need for art. You could just write an essay or something instead.

MD: Right, yeah, exactly. (laughs) Whenever I explain it, I get bummed out about making it and then I usually change whatever that idea was. (laughs) I like the whole idea of it being open-ended, where the viewer gets to decide really what’s happening to themselves. Sometimes their stories are much more interesting than what I’m trying to tell. (laughs)

L&M: Are you trying then, instead of asking someone to figure out your story, trying to push buttons in the viewer to get their stories to surface?

MD: Yeah, I like that idea. (laughs) I don’t know if I’m doing it, but I do like that – wake up a story out of them.

L&M: Your work often addresses the concept of masculinity, sometimes represented as a cowboy – you said about the cowboy character in the Guardian, “That’s me trying to grasp whatever masculinity I had. I always drew them amputated because I felt not as macho.” You also put strong women in the role of protagonist, and men as “backup dancers.” You clearly have an admiration of strong women, such as your friends and your wife. Why is this a driving theme in your work?

MD: I spent half a year in this small town, Fosston, Saskatchewan [Canada], going to high school and it was kind of this cowboy culture that I wasn’t quite of aware of before. I guess I was a little bit in Winnipeg. I was always kind of a skinny, scrawny, nerd kid drawing in class. I usually identified with being an amputee of some sort, just not being good at sports or anything like that, or even being into what anyone was talking about sports-wise. And then I find in general, all the sexism really repulses me, and the violence against women in society is so, it’s hard to even believe the things that are still being said in politics now regarding women’s rights. There are moments I’ve seen abuse against women and that has always affected me as well. It’s hard to pick up the newspaper and not see some aggression against [women]. I was always impressed by strong women. They have it much harder than a white man. (laughs)

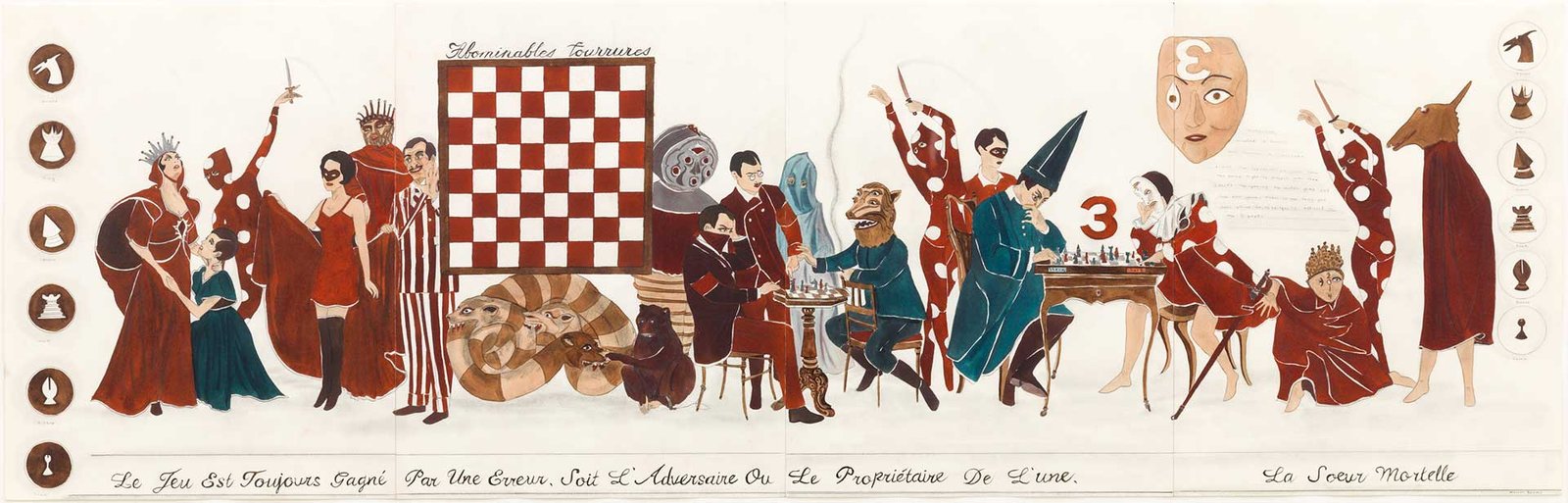

Marcel Dzama, “The Fatal Sister.” (2014) Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper. 4 part work. Overall: 14 x 44 inches (35.6 x 111.8 cm).

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5