Anders Nilsen

Interview

Drawing a world is the next best thing to inhabiting it.

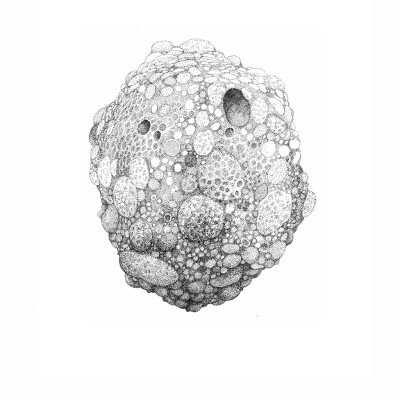

L&M: You work a lot in your sketchbooks, but because your blog as well as your published work often features actual sketchbook pages – Poetry is UselessPoetry is Useless (Drawn & Quarterly, 2015) In Poetry is Useless, Anders Nilsen redefines the sketchbook format, intermingling elegant, densely detailed renderings of mythical animals, short comics drawn in ink, meditations on religion, and abstract shapes and patterns. Page after page gives way under Nilsen’s deft hatching and perfectly placed pen strokes, revealing his intellectual curiosity and wry outlook on life’s many surprises. (via Drawn & Quarterly) is almost entirely made up of your sketchbooks – how much of it feels like true sketching?

In Poetry is Useless, Anders Nilsen redefines the sketchbook format, intermingling elegant, densely detailed renderings of mythical animals, short comics drawn in ink, meditations on religion, and abstract shapes and patterns. Page after page gives way under Nilsen’s deft hatching and perfectly placed pen strokes, revealing his intellectual curiosity and wry outlook on life’s many surprises. (via Drawn & Quarterly) is almost entirely made up of your sketchbooks – how much of it feels like true sketching?

AN: There’s probably an element of self-deception in it. (laughs) For the last several years of working in my sketchbooks, I have kept a regular blog where I’m posting sketchbook drawings, so I am thinking of them as potential finished pieces, and generally not as the potential beginning of a graphic novel or something. But as I’m working in my sketchbook, playing around in there, sort of just entertaining myself, I am thinking about an audience and how a reader will engage with it or be interested in it. So I’m trying to make it fun, not just for myself but for the reader. The stuff that then ends up turning into a longer, larger project – that’s really not really intentional at the start. So for example at the moment I’m working on a graphic novel that sort of came out of a small dialogue that I wrote in my sketchbook that I had no plans for. And It’s just one of those things that kind of stuck in my brain that feels like it’s gonna lead to other things.

L&M: This is your current work that will presumably come out after Poetry is Useless?

AN: Yeah, I may end up serializing it.

L&M: What is this new work about? Or is it still a secret?

AN: It’s in very early stages. I’m just figuring it out now, but it partly is growing out of the PrometheusPrometheusPrometheus is a Titan in Greek mythology, best known as the deity in Greek mythology who was the creator of mankind and its greatest benefactor, who gifted mankind with fire stolen from Mount Olympus. (wiki) story from Rage of PoseidonRage of Poseidon (Drawn & Quarterly, 2013) Rage of Poseidon brings all of the philosophical depth of Nilsen’s earlier work to bear on contemporary society, asking how a twenty-first century child might respond to being sacrificed on a mountaintop, and probing the role gods like Venus and Bacchus might have in the world of today. Nilsen works in a unique style for these short stories, distilling individual moments in black silhouette on a spare white background. Above all, though, he immerses us seamlessly in a world where gods and humans are more alike than not, forcing us to recognize the humor in our (and their) desperation. (via Drawn & Quarterly). I’m interested in figuring out what he and the eagle talk about everyday. The classic Prometheus story is Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, one of the ancient greek playwrights. It was just one of three plays, but the others were lost. But there’s some sense among historians of what they were about, and how the story ends. So I’m going to play with that. But there’s a bunch of other elements in there as well. Some characters from Dogs and Water might appear. We’ll see.

Rage of Poseidon brings all of the philosophical depth of Nilsen’s earlier work to bear on contemporary society, asking how a twenty-first century child might respond to being sacrificed on a mountaintop, and probing the role gods like Venus and Bacchus might have in the world of today. Nilsen works in a unique style for these short stories, distilling individual moments in black silhouette on a spare white background. Above all, though, he immerses us seamlessly in a world where gods and humans are more alike than not, forcing us to recognize the humor in our (and their) desperation. (via Drawn & Quarterly). I’m interested in figuring out what he and the eagle talk about everyday. The classic Prometheus story is Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, one of the ancient greek playwrights. It was just one of three plays, but the others were lost. But there’s some sense among historians of what they were about, and how the story ends. So I’m going to play with that. But there’s a bunch of other elements in there as well. Some characters from Dogs and Water might appear. We’ll see.

L&M: Speaking of audience, was drawing and comics a response to losing your audience after art school?

AN: In part. When you’re in art school you have an audience. Whether it’s the audience you want or respect or care what they think, it doesn’t matter, they’re just there. Like the teachers you have, even if you feel feel like you are too good for the place, you’re still reacting to that built-in audience. When that disappeared it forced me to rethink why I was making art and who I want to make it for. What kind of conversation do I want to have with the world? And that was dislocating at first, because all of a sudden you don’t have an audience which… As much as we like to think of art being for arts sake or for for personal expression or we have these romantic ideas about art and the individual, the truth is, it is about connection and it is about having some kind of social, cultural conversation.

L&M: Coming from art school do you feel the medium of writing and comics allowed for more connection and conversation? Is that why you were ultimately drawn away from painting and to that medium?

AN: Yeah, I think one of the reasons I gravitated towards comics is because a concern with the audience and that interaction is foregrounded. You are making products that are going out into the world, with commerce being an explicit part of the equation. And it’s like, if you’re telling a joke, the joke isn’t finished until somebody laughs at it.

…I mean I guess I just don’t understand why you wouldn’t think about an audience. It’s like if you’re making a painting, clearly you’re making it for someone to look at, or if you’re creating an installation, you’re creating it for someone to walk through it and experience it, but I think there is more of a mythology around those kinds of mediums that emphasize the artist, him or herself, and their internal monologue, their “theory” which I just think is silly. (laughs) Like, we’re human, we’re social creatures, conversations are way more interesting than talking to yourself.

L&M: The romanticized notion of the artist often emphasizes the genius of the artist, and generally speaking, one is meant to admire a great artist or a great work of art and less to interact with it, especially compared to the symbiotic relationship between a writer and a reader.

AN: Right, I think the corollary of that egotism is that they may be really good at putting their vision out into the world, and it might be a really, really strong vision. But yeah, what you’re saying totally resonates with me. My style of drawing sort of shifts with every book I do. For me it’s not about having a very particular idiosyncratic personal style. It’s about getting the ideas down.

[foogallery id=”6571″]

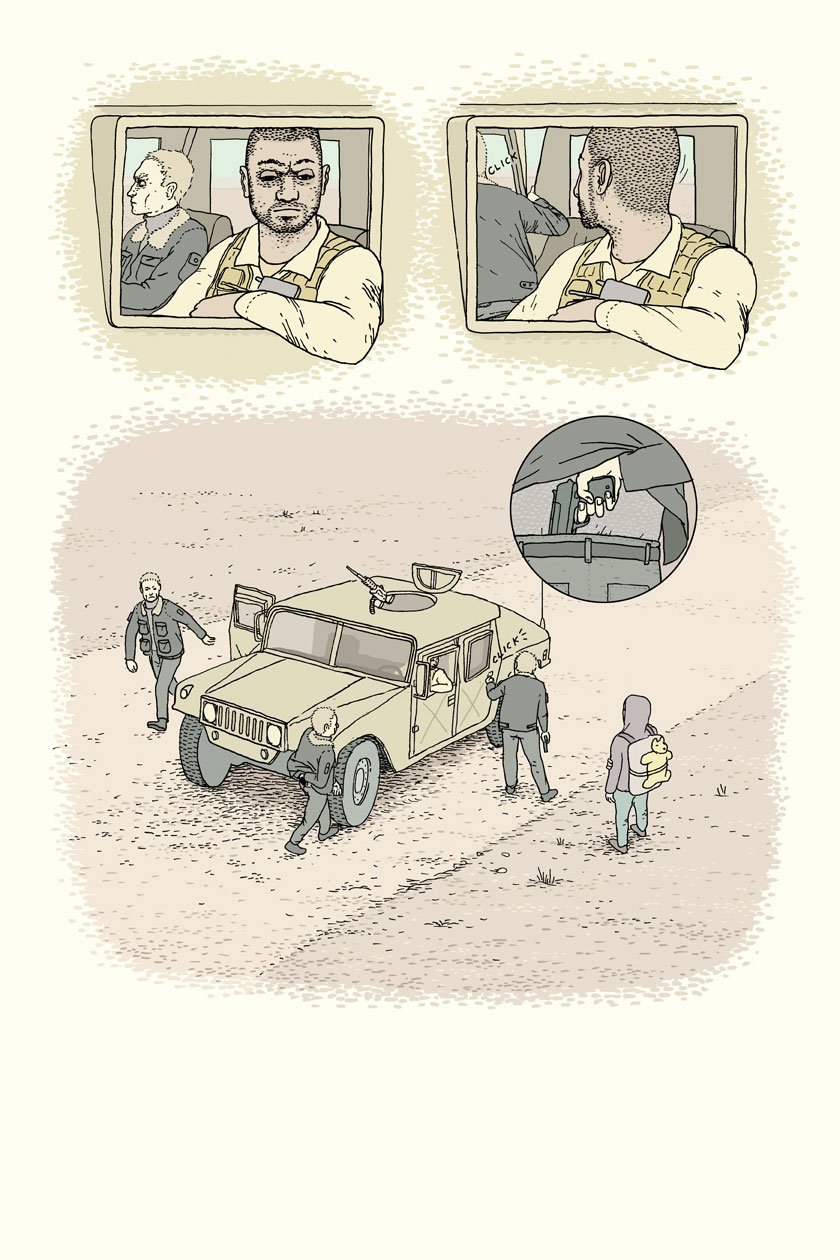

Anders Nilsen, “Poetry is Useless.” (Drawn & Quarterly, 2015)

[foogallery id=”6545″]

Anders Nilsen, Original Sketchbooks

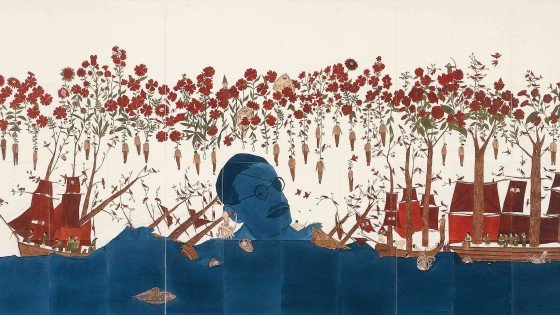

[foogallery id=”6723″]

Pages from Anders Nilsen’s “God and the Devil at War in the Garden.” (Self-published, 2014) Ink on Paper. (middle page: collaboration with Chicago novelist Kyle Beachy)

Anders Nilsen, “Fawn in Upturned Roots.” (2007) Gouache on Board.

And the truth is, if you pay any attention at all to the art market now, it’s a crazy Disneyland for rich people.

L&M: Are ideas then the driving force? With the silhouetted talking head, for example, the emphasis is more on the words and ideas, but you also have drawings which are very lush and beautiful. When do you go into a more sketchy mode and when do you decide to do a more artistic and beautifully rendered drawings?

AN: When the drawing is simpler, it’s usually because I don’t know exactly where I’m going with it and I want to get the ideas down and sort of tell the story or make the points as quickly and in as a concise a way as possible. And usually those pieces are less about story and more about a little idea or a little poetic image. Whereas the works that I’ve done where the drawing is more involved, like Big Questions or Dogs and Water… It’s like I’m trying to bring a reader into a world and so I want to create more of an atmosphere and more of the feeling of getting drawn in and getting lost in an actual world. In that case I’m still trying to get ideas across, but I’m also trying to seduce the reader a little bit and absorb them a little more.

L&M: Could a way to look at it be, that in the more simple drawings, where you’re waxing philosophical or political or making some kind of social commentary, it’s a very cerebral mode that you’re in, whereas the atmospheric quiet scenes that you draw are much more meditative and about feeling?

AN: Exactly. A lot of the stuff in my sketchbooks, the little comics with the silhouetted head and even some of the work in The EndThe End (Fantagraphics, 2103) Assembled from work done in Anders Nilsens sketchbooks over the course of the year following the death of his fiancée in 2005, The End is a collection of short strips about loss, paralysis, waiting, and transformation. It is a concept album in different styles, a meditation on paying attention, an abstracted autobiography and a travelogue, reflecting the progress of his struggle to reconcile the great upheaval of a death, and finding a new life on the other side. (via Fantagraphics), is a little bit more about poking and prodding the reader and being provocative and so that blank face in some ways can be a little bit of a wall. It’s just slower, doing real drawing and creating a world for the reader to be immersed in. There’s pleasure in that for me too, because drawing a world is the next best thing to inhabiting it. I mean this goes back to audience a little bit. I do want to provoke people a little bit and try to get them to think about things differently or whatever, but I really do love… Like I want to give them a little gift too. I want them to really enjoy the world that I’m creating. I feel like TV shows have started doing this a little more, too, but when I was in undergrad I took a Shakespeare class and I remember the instructor talking about the fact that a lot of those plays are written on two levels. He would often write the same idea down twice in a dialogue, one in a way that was sort of literary, a way that the nobility or the rich people would appreciate, and once in a more vernacular, simple way, or even a crass, bawdy way. A lot of his plays are dealing with pretty heavy broad philosophical issues, but they’re also just really compelling soap operas, and that’s totally what I’m interested in doing, entertaining people, and also sliding in some other provocative ideas, or nudge people to think about things in ways that they might not otherwise.

Assembled from work done in Anders Nilsens sketchbooks over the course of the year following the death of his fiancée in 2005, The End is a collection of short strips about loss, paralysis, waiting, and transformation. It is a concept album in different styles, a meditation on paying attention, an abstracted autobiography and a travelogue, reflecting the progress of his struggle to reconcile the great upheaval of a death, and finding a new life on the other side. (via Fantagraphics), is a little bit more about poking and prodding the reader and being provocative and so that blank face in some ways can be a little bit of a wall. It’s just slower, doing real drawing and creating a world for the reader to be immersed in. There’s pleasure in that for me too, because drawing a world is the next best thing to inhabiting it. I mean this goes back to audience a little bit. I do want to provoke people a little bit and try to get them to think about things differently or whatever, but I really do love… Like I want to give them a little gift too. I want them to really enjoy the world that I’m creating. I feel like TV shows have started doing this a little more, too, but when I was in undergrad I took a Shakespeare class and I remember the instructor talking about the fact that a lot of those plays are written on two levels. He would often write the same idea down twice in a dialogue, one in a way that was sort of literary, a way that the nobility or the rich people would appreciate, and once in a more vernacular, simple way, or even a crass, bawdy way. A lot of his plays are dealing with pretty heavy broad philosophical issues, but they’re also just really compelling soap operas, and that’s totally what I’m interested in doing, entertaining people, and also sliding in some other provocative ideas, or nudge people to think about things in ways that they might not otherwise.

L&M: Is this an influence from your art school training? You tend to talk about your comics using vocabulary and discourse about art-making.

AN: I probably think in a certain way about what I’m doing because of my art education. But the truth is, my art education and a lot of art education is really not interested in the soap opera part. That’s “genre,” not literature. The genre versus literature distinction is useful but each one needs the other a little bit. If you exist only in one camp your work is likely to get either boring or embarrassing. Typically genre means popular categories of stories: the western, sci-fi, superheroes, adventure, romance, etc. Literary forms on the other hand are, the quote-unquote “higher” forms, like I don’t know, Jonathan Franzen or Emily Dickenson or whatever.

L&M: Do you think because of that, high-art has lost its resonance with some, or do you question what its value is?

AN: I do question what it’s value is, which is not the same thing as saying it has no value. I think it can have value, for sure. I mean there’s a reason why it’s called “high-art,” and this is sort of an impolite thing to say, but high-art is what it is because it is for the rich. Ever since the Renaissance… It’s like if you walk around in museums in Europe, not the big museums necessarily, but the small city museums, they are filled with painting. Endless portraits and still-lifes and landscapes. And those paintings were made because there was a market for them. There hadn’t been a lot of wealth in Europe before that time. All of a sudden there was all this wealth and they needed stuff to buy to show off all their wealth. And the truth is, if you pay any attention at all to the art market now, it’s a crazy Disneyland for rich people. (laughs) People are buying paintings and putting them in warehouses and hoping they appreciate in value. So that’s the thing, that’s an important part of what high-art is and always has been to some extent. Well the thing that happens is some of that stuff is actually amazing, right? So like you go to those city museums in Europe and they’re filled with stuff that’s technically amazing, but kind of boring as art. But then you go to the UffiziUffizi GalleryThe Uffizi Gallery (Italian: Galleria degli Uffizi) is an art museum in Italy. It is located in Florence, and is one of the oldest and most famous art museums in the world. The building of Uffizi was begun by Giorgio Vasari in 1560 for Cosimo I de" Medici so as to accommodate the offices of the Florentine magistrates, hence the name uffizi, "offices". The construction was later continued by Alfonso Parigi and Bernardo Buontalenti and completed in 1581. (wiki) in Florence or you go to the LouvreLouvreThe Louvre or the Louvre Museum (French: Musée du Louvre) is one of the world"s largest museums and a historic monument in Paris, France. A central landmark of the city, it is located on the Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement (district). Nearly 35,000 objects from prehistory to the 21st century are exhibited over an area of 60,600 square metres (652,300 square feet). The Louvre is the world"s most visited museum, and received more than 9.7 million visitors in 2012. (wiki) or whatever, and you can find some truly great work, depending on your taste I suppose. But like, some of the pieces that art historians have plucked out and put the spotlight on, there’s a good reason. They’re fucking amazing. So… I don’t know what this has to do with me. (laughs) I mean, I don’t think it makes sense to say high-art has function x, y and z, and it is failing to perform this function in the contemporary scene. You know, part of it’s function is as a market commodity. It’s carrying out that function just fine.

L&M: The question has more to do with your reaction to all that. Are these some of the reasons why you decided to move to a more democratic, audience-centric medium?

AN: Yeah, but also I went to art school. That was the water that I learned to swim in too, high-art discourse. But on the other hand I’m like a lower middle-class kid who grew up reading comics, so that’s the work that speaks to me. But because of my education and because I’m interested in these questions, I sort of can’t help but think about what I do using that language and those frameworks that high-art has handed down. And I’m fine with that. Maybe it’s sounds like a contradiction, or, like, a paradox, but I like paradoxes.

L&M: That said, you’ve have kept, maybe if not a whole foot, a toe in the art world. Do you still have art-world aspirations?

AN: Yeah definitely, you know like I said, some of that stuff is amazing, and it’s amazing because those artists are doing what they can to think super-deeply about their work. Or you know it’s like the kind of art that a museum allows to exist, that kind of thing can’t really exist anywhere else. It’s like, in the Renaissance, there had never before been a place to paint a ceiling as big as the Sistine ChapelThe Sistine Chapel The Sistine Chapel (Latin: Sacellum Sixtinum; Italian: Cappella Sistina) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the Pope, in Vatican City. Originally known as the Cappella Magna, the chapel takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who restored it between 1477 and 1480. Since that time, the chapel has served as a place of both religious and functionary papal activity. Today it is the site of the Papal conclave, the process by which a new pope is selected. The fame of the Sistine Chapel lies mainly in the frescos that decorate the interior, and most particularly the Sistine Chapel ceiling and The Last Judgment by Michelangelo. (wiki). That new market created the possibility for that to happen, and it’s amazing. It’s one of the most amazing things that’s ever been made. So I guess I’m ambivalent a bit about it, but yeah, I definitely do have one foot, or one toe, in that world at least.

The Sistine Chapel (Latin: Sacellum Sixtinum; Italian: Cappella Sistina) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the Pope, in Vatican City. Originally known as the Cappella Magna, the chapel takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who restored it between 1477 and 1480. Since that time, the chapel has served as a place of both religious and functionary papal activity. Today it is the site of the Papal conclave, the process by which a new pope is selected. The fame of the Sistine Chapel lies mainly in the frescos that decorate the interior, and most particularly the Sistine Chapel ceiling and The Last Judgment by Michelangelo. (wiki). That new market created the possibility for that to happen, and it’s amazing. It’s one of the most amazing things that’s ever been made. So I guess I’m ambivalent a bit about it, but yeah, I definitely do have one foot, or one toe, in that world at least.

[foogallery id=”6729″]

Anders Nilsen, “The End.” (Fantagraphics, 2013)

[foogallery id=”6593″]

Wall drawing for “Cartoonink!” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Sullivan Galleries. 2011. Acrylic on drywall.

Installation shot of “Big Questions” exhibition at Fumetto, Lucerne Switzerland, 2013.