Lines & Marks: On your blog you wrote, “Sometimes I make comics, sometimes I do illustration, sometimes I make diagrams and sometimes I make ‘paintings’… but everything I do is drawing. Drawing is everything.” Could you expound upon that and also talk about what your drawing practice is?

Anders Nilsen: I don’t know if I really have a routine. I try to draw in my sketchbooks semi-regularly, but I don’t do it everyday. I do it much more when I’m traveling, when I have forced free time and am waiting a lot. I guess part of what that quote means is… let’s see… I’m gonna try to articulate this and we’ll see how it turns out… (laughs) The distinction between drawing and painting for me is that painting is about the creation of a finished object, the corollary being that it’s a thing for sale. Drawing is more a process of thinking and seeing and so it’s all about investigating and trying to make a physical record of a thing that’s in your brain, or that’s in front of your face that you’re looking at. So to me, drawing is much more about seeing and trying to understand the world. Some of the drawing I do is in my sketchbook, some is doing thumbnails for comics, some of it is the drawing of the comics, but it’s always about some sort of investigation, trying to make a thing happen, trying to articulate thought.

L&M: Drawing then is more a mode of figuring things out?

AN: Right. You’re allowed to fuck up when you’re drawing, you’re allowed to get it wrong, and sometimes that’s the way that you discover something interesting.

L&M: Speaking of fuck-ups, you don’t pencil first, but instead you draw in ink and use a lot of liquid paper to correct.

AN: (laughs) Right. Well I don’t actually use liquid paper anymore. I use white ink now. Liquid paper isn’t archival.

L&M: I don’t know if this was conscious or not, but there is a loose parallel between drawing directly in pen and the subsequent process of making mistakes and corrections and your book, Don’t Go Where I Can’t FollowDont Go Where I Cant Follow In this collection of letters, drawings, and photos, Anders Nilsen chronicles a six-year relationship and the illness that brought it to an end. Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow is an eloquent appreciation of the time the author shared with his fiancée, Cheryl Weaver. The story is told using artifacts of the couple’s life together, including early love notes, simple and poetic postcards, tales of their travels in written and comics form, journal entries, and drawings done in the hospital in her final days. It concludes with a beautifully rendered account of Weaver’s memorial that Glen David Gold, writing in the Los Angeles Times, called “16 panels of beauty and grace.” Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow is a deeply personal romance, and a universal reminder of our mortality and the significance of the relationships we build. (via Drawn & Quarterly). The whole story from beginning to end was a long series mistakes and corrections, with one exception – the spreading of the Cheryl’s ashes. And with that final act everything went right. It’s not really a solid question I realize. (laughs) Is there any comment you might have on that?

In this collection of letters, drawings, and photos, Anders Nilsen chronicles a six-year relationship and the illness that brought it to an end. Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow is an eloquent appreciation of the time the author shared with his fiancée, Cheryl Weaver. The story is told using artifacts of the couple’s life together, including early love notes, simple and poetic postcards, tales of their travels in written and comics form, journal entries, and drawings done in the hospital in her final days. It concludes with a beautifully rendered account of Weaver’s memorial that Glen David Gold, writing in the Los Angeles Times, called “16 panels of beauty and grace.” Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow is a deeply personal romance, and a universal reminder of our mortality and the significance of the relationships we build. (via Drawn & Quarterly). The whole story from beginning to end was a long series mistakes and corrections, with one exception – the spreading of the Cheryl’s ashes. And with that final act everything went right. It’s not really a solid question I realize. (laughs) Is there any comment you might have on that?

AN: I like the connection you’re making. The first thing I’ll say is that, yeah, Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow was specifically thought of that way. Cheryl and I had a history of taking trips that always went awry in some way or other. Before she ever got sick I had an idea about doing a little zine about messed up travel stories. So yeah, very perceptive. I think it’s super important to embrace mistakes. That’s where life happens. And those are the stories that ended up being worth telling, because they’re sort of funny and they’re interesting and they’re unexpected and I think you can certainly say the same thing about art that gets created that way.

I do pencil now a little bit, though. The reason originally that I stopped pencilling before I went to inks was that I felt like when I would pencil a panel first, when I would ink it, I would end up tracing, not drawing, and so the lines just weren’t alive the way I wanted them to be. But after working on Big QuestionsBig Questions A haunting postmodern fable, Big Questions is the magnum opus of Anders Nilsen, one of the brightest and most talented young cartoonists working today. This beautiful and minimalist story, collected here for the first time, is the culmination of ten years and over 600 pages of work that details the metaphysical quandaries of the occupants of an endless plain, existing somewhere between a dream and a Russian steppe. (via Drawn & Quarterly) for ten years I learned to draw better and I could be more present in the inking. My pencilling is still super loose so there ends up being a lot of whiting stuff out or cutting and pasting. This is something I’ve started grappling with with my students at MCADMCADThe Minneapolis College of Art and Design is a private, nonprofit four-year and postgraduate college specializing in the visual arts. Located in the Whittier neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, MCAD currently enrolls approximately 700 students offering education in painting, drawing, advertising, entrepreneurial studies, sculpture, printmaking, papermaking, photography, video, illustration, graphic design, book arts, furniture design, liberal arts, comic art, and sustainable design. MCAD is one of just a few major art schools to offer a major in comic art. (wiki). I think it’s super important to be open to fixing stuff, changing it, editing it. People who are into comics tend to be a little precious about their drawing. It’s like they spent all this time learning how to draw really well they don’t want to show themselves drawing shitty, so everything has to be perfect, and they want it to be perfect the first time. And comics are inherently difficult to edit because you can’t add or take away a panel without shifting every panel in the entire book. You have to build editing into your process or be willing to go with whatever your first try is, which usually isn’t very good.

A haunting postmodern fable, Big Questions is the magnum opus of Anders Nilsen, one of the brightest and most talented young cartoonists working today. This beautiful and minimalist story, collected here for the first time, is the culmination of ten years and over 600 pages of work that details the metaphysical quandaries of the occupants of an endless plain, existing somewhere between a dream and a Russian steppe. (via Drawn & Quarterly) for ten years I learned to draw better and I could be more present in the inking. My pencilling is still super loose so there ends up being a lot of whiting stuff out or cutting and pasting. This is something I’ve started grappling with with my students at MCADMCADThe Minneapolis College of Art and Design is a private, nonprofit four-year and postgraduate college specializing in the visual arts. Located in the Whittier neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, MCAD currently enrolls approximately 700 students offering education in painting, drawing, advertising, entrepreneurial studies, sculpture, printmaking, papermaking, photography, video, illustration, graphic design, book arts, furniture design, liberal arts, comic art, and sustainable design. MCAD is one of just a few major art schools to offer a major in comic art. (wiki). I think it’s super important to be open to fixing stuff, changing it, editing it. People who are into comics tend to be a little precious about their drawing. It’s like they spent all this time learning how to draw really well they don’t want to show themselves drawing shitty, so everything has to be perfect, and they want it to be perfect the first time. And comics are inherently difficult to edit because you can’t add or take away a panel without shifting every panel in the entire book. You have to build editing into your process or be willing to go with whatever your first try is, which usually isn’t very good.

I think it’s super important to embrace mistakes. That’s where life happens.

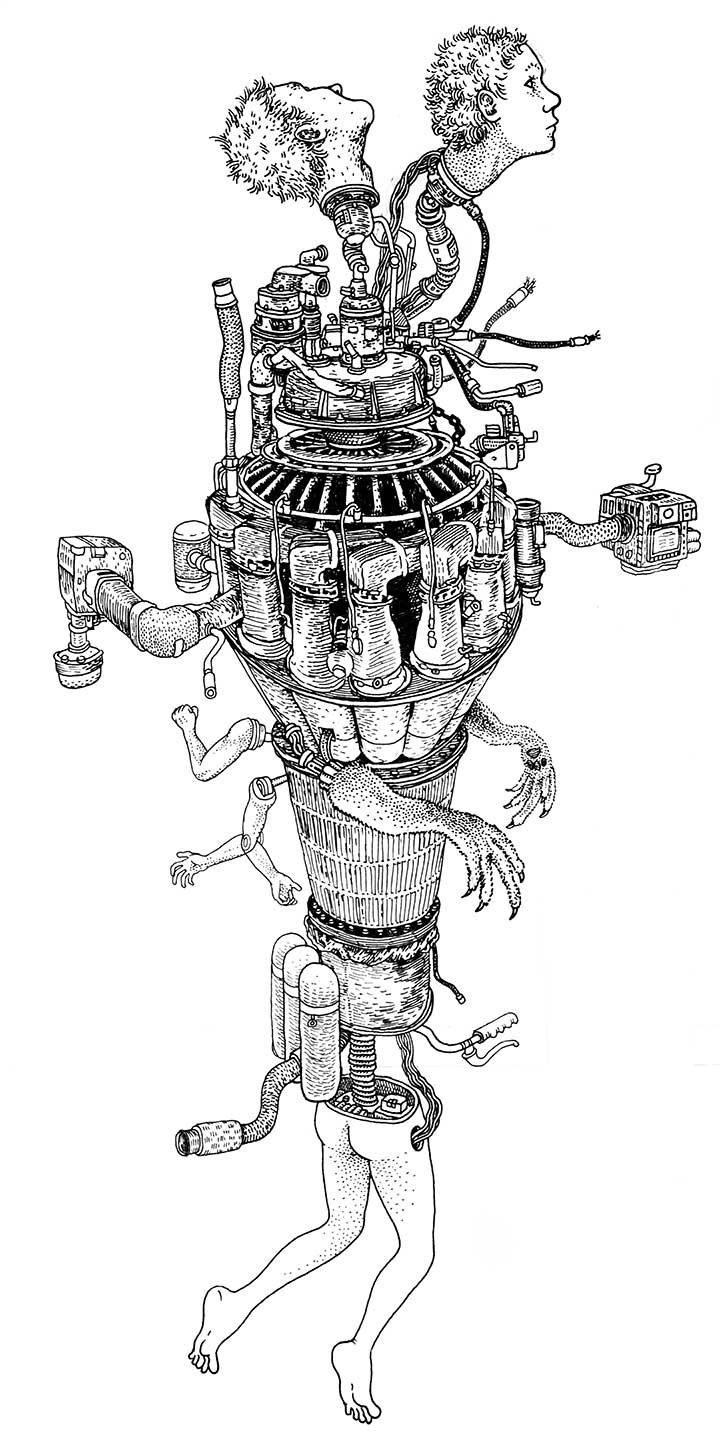

[foogallery id=”6542″]

Corrected Panels from Anders Nilsen’s “Big Questions.” (Drawn & Quarterly, 2011)

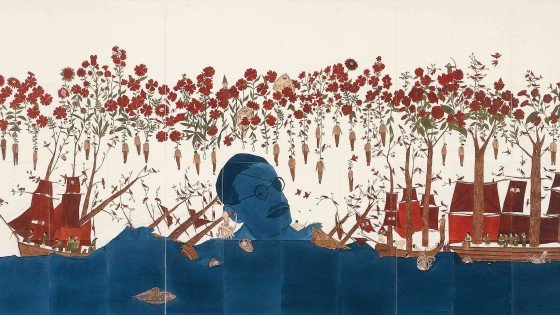

[foogallery id=”6561″]

Scene from “Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow.” (Drawn & Quarterly, 2006)

Cover painting for the French translation of Dogs and Water & Sisyphus, “Des chiens, de l’eau.” 2005. Gouache on Paper.

You’re allowed to fuck up when you’re drawing, you’re allowed to get it wrong, and sometimes that’s the way that you discover something interesting.

L&M: And back to this parallel, if you were just now talking about life, it would be also good advice.

AN: (laughs) Yeah, you’re probably not going to get everything right the first time.

L&M: So one is probably more likely to make mistakes trying to avoid them, or if one is too precious about their work, or too concerned how everything should or will turn out.

AN: Yeah, if you know what the end product is going to be at the beginning, then what’s the point of making it? For me that’s important, I don’t want to know what I’m doing until it’s done and I’m looking back.

L&M: Is there a danger of working that way, which might be a weak plot, or having gone off in too many directions, or not being able to wrap it up, etc.?

AN: There are different kinds of knowing I guess. Somewhere in my brain, I think I do know. And I’m trying to not let that part of my brain talk to the other part of my brain. I want the conscious part of my brain to be able to open a little window and look inside the other part, but it’s kind of dark… This metaphor isn’t gonna work. (laughs) Like you have a sense as you’re working of what feels right, like should this character do x or should this character do y? And you might not know at first, but if you sit with it for a while and you draw another scene that reveals a little bit about the character then it’ll be pretty clear after a minute. The character clearly is gonna do x because that’s the kind of person that character is. I mean, it’s like the way Michelangelo would talk about carving marble. It was like he could see the figure inside the marble and he had to cut away the right parts. On some level, that’s sort of an interesting metaphor for the art making process, but in some way as he’s doing it, he’s still seeing, his vision of that thing is getting refined more and more. I feel like that’s true for me. I can see the story, but it’s behind a screen, so I can’t see it that well. But as I work on it, it gets a little clearer and get a little clearer.

L&M: Does it happen, where you might have worked on something for a long time and then realized that it’s not gonna work and you have to scrap it?

AN: Oh yeah. (laughs) With Dogs and WaterDogs and Water Dogs and Water chronicles a piece of a lonely journey, without origin or destination. A young man wandering a nameless path has only a stuffed bear as a companion, which inertly endures his desperation, anger and musings along the way. Dogs & Water received an Ignatz award for "Outstanding Story" and has been translated into several languages. (via Drawn & Quarterly), I threw away 25 pages at some point. I’m better at it now. I can see the story a little better. It’s a skill. It’s a thing that you get better at, discerning the shape behind the screen. So hopefully I’m not going to be throwing double-digits worth of pages away from this book. We’ll see. (laughs)

Dogs and Water chronicles a piece of a lonely journey, without origin or destination. A young man wandering a nameless path has only a stuffed bear as a companion, which inertly endures his desperation, anger and musings along the way. Dogs & Water received an Ignatz award for "Outstanding Story" and has been translated into several languages. (via Drawn & Quarterly), I threw away 25 pages at some point. I’m better at it now. I can see the story a little better. It’s a skill. It’s a thing that you get better at, discerning the shape behind the screen. So hopefully I’m not going to be throwing double-digits worth of pages away from this book. We’ll see. (laughs)

L&M: There’s that idiom that you have to learn to kill your babies.

AN: Oh yeah, yeah. It’s true, you just have to be ruthless. It might be a beautiful drawing, but if it doesn’t work for the story, it’s just, you know… That’s the beautiful thing about the internet and having a blog, you can just put it on your blog and be like, look at this other thing I did that didn’t work out. (laughs) In the big [Drawn & Quarterly] 25th anniversary bookDrawn & Quarterly 25 Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels is an eight hundred-page thank-you letter to the cartoonists whose steadfast belief in a Canadian micro-publisher never wavered. In 1989, a prescient Chris Oliveros created D+Q with a simple mandate to publish the world’s best cartoonists. Thanks to his taste-making visual acumen and the support of over fifty cartoonists from the past two decades, D+Q has grown from an annual stapled anthology into one of the world"s leading graphic novel publishers. (via Drawn & Quarterly), I published eight pages from Dogs and Water that got cut 10 years ago.

Drawn & Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels is an eight hundred-page thank-you letter to the cartoonists whose steadfast belief in a Canadian micro-publisher never wavered. In 1989, a prescient Chris Oliveros created D+Q with a simple mandate to publish the world’s best cartoonists. Thanks to his taste-making visual acumen and the support of over fifty cartoonists from the past two decades, D+Q has grown from an annual stapled anthology into one of the world"s leading graphic novel publishers. (via Drawn & Quarterly), I published eight pages from Dogs and Water that got cut 10 years ago.

L&M: Sort of like outtakes?

AN: Kind of an outtake, which I have mixed feelings about doing at all, but if you can’t actually kill your babies and you can only lock them in a closet, then its nice to be able to take them out once in a while and show them. (laughs). Wow, that’s a terrible metaphor.